Junctions and channels

Junctions make it possible to send the messages to different channels, process the messages differently on each channel, and then join every channel together again. You can define any number of channels in a junction: every channel receives a copy of every message that reaches the junction. Every channel can process the messages differently, and at the end of the junction, the processed messages of every channel return to the junction again, where further processing is possible.

A junction includes one or more channels. A channel usually includes at least one filter, though that is not enforced. Otherwise, channels are identical to log statements, and can include any kind of objects, for example, parsers, rewrite rules, destinations, and so on. (For details on using channels, as well as on using channels outside junctions, see Using channels in configuration objects.)

|

|

NOTE:

Certain parsers can also act as filters:

|

You can also use log-path flags in the channels of the junction. Within the junction, a message is processed by every channel, in the order the channels appear in the configuration file. Typically if your channels have filters, you also set the flags(final) option for the channel. However, note that the log-path flags of the channel apply only within the junction, for example, if you set the final flag for a channel, then the subsequent channels of the junction will not receive the message, but this does not affect any other log path or junction of the configuration. The only exception is the flow-control flag: if you enable flow-control in a junction, it affects the entire log path. For details on log-path flags, see Log path flags.

junction {

channel { <other-syslog-ng-objects> <log-path-flags>};

channel { <other-syslog-ng-objects> <log-path-flags>};

...

};

Example: Using junctions

For example, suppose that you have a single network source that receives log messages from different devices, and some devices send messages that are not RFC-compliant (some routers are notorious for that). To solve this problem in earlier versions of syslog-ng OSE, you had to create two different network sources using different IP addresses or ports: one that received the RFC-compliant messages, and one that received the improperly formatted messages (for example, using the flags(no-parse) option). Using junctions this becomes much more simple: you can use a single network source to receive every message, then use a junction and two channels. The first channel processes the RFC-compliant messages, the second everything else. At the end, every message is stored in a single file. The filters used in the example can be host() filters (if you have a list of the IP addresses of the devices sending non-compliant messages), but that depends on your environment.

log {

source {

syslog(

ip(10.1.2.3)

transport("tcp")

flags(no-parse)

);

};

junction {

channel {

filter(f_compliant_hosts);

parser {

syslog-parser();

};

};

channel {

filter(f_noncompliant_hosts);

};

};

destination {

file("/var/log/messages");

};

};

Since every channel receives every message that reaches the junction, use the flags(final) option in the channels to avoid the unnecessary processing the messages multiple times:

log {

source {

syslog(

ip(10.1.2.3)

transport("tcp")

flags(no-parse)

);

};

junction {

channel {

filter(f_compliant_hosts);

parser {

syslog-parser();

};

flags(final);

};

channel {

filter(f_noncompliant_hosts);

flags(final);

};

};

destination {

file("/var/log/messages");

};

};

Note that syslog-ng OSE has several parsers that you can use to parse non-compliant messages. You can even write a custom syslog-ng parser in Python. For details, see parser: Parse and segment structured messages.

|

|

NOTE:

Junctions differ from embedded log statements, because embedded log statements are like branches: they split the flow of messages into separate paths, and the different paths do not meet again. Messages processed on different embedded log statements cannot be combined together for further processing. However, junctions split the messages to channels, then combine the channels together. |

An alternative, more straightforward way to implement conditional evaluation is to configure conditional expressions using if {}, elif {}, and else {} blocks. For details, see if-else-elif: Conditional expressions.

Log path flags

Flags influence the behavior of syslog-ng, and the way it processes messages. The following flags may be used in the log paths, as described in Log paths.

| Flag | Description |

|---|---|

| catchall | This flag means that the source of the message is ignored, only the filters of the log path are taken into account when matching messages. A log statement using the catchall flag processes every message that arrives to any of the defined sources. |

| drop-unmatched | This flag means that the message is dropped along a log path when it does not match a filter or is discarded by a parser. Without using the drop-unmatched flag, syslog-ng OSE would continue to process the message along alternative paths. |

| fallback |

This flag makes a log statement 'fallback'. Fallback log statements process messages that were not processed by other, 'non-fallback' log statements. 'Processed' means that every filter of a log path matched the message. Note that in the case of embedded log paths, the message is considered to be processed if it matches the filters of the outer log path, even if it does not match the filters of the embedded log path. For details, see Example: Using log path flags. |

| final |

This flag means that the processing of log messages processed by the log statement ends here, other log statements appearing later in the configuration file will not process the messages processed by the log statement labeled as 'final'. Note that this does not necessarily mean that matching messages will be stored only once, as there can be matching log statements processed before the current one (syslog-ng OSE evaluates log statements in the order they appear in the configuration file). 'Processed' means that every filter of a log path matched the message. Note that in the case of embedded log paths, the message is considered to be processed if it matches the filters of the outer log path, even if it does not match the filters of the embedded log path. For details, see Example: Using log path flags. |

| flow-control | Enables flow-control to the log path, meaning that syslog-ng will stop reading messages from the sources of this log statement if the destinations are not able to process the messages at the required speed. If disabled, syslog-ng will drop messages if the destination queues are full. If enabled, syslog-ng will only drop messages if the destination queues/window sizes are improperly sized. For details, see Managing incoming and outgoing messages with flow-control. |

|

|

Caution:

The final, fallback, and catchall flags apply only for the top-level log paths, they have no effect on embedded log paths. |

Example: Using log path flags

Let's suppose that you have two hosts (myhost_A and myhost_B) that run two applications each (application_A and application_B), and you collect the log messages to a central syslog-ng server. On the server, you create two log paths:

-

one that processes only the messages sent by myhost_A, and

-

one that processes only the messages sent by application_A.

This means that messages sent by application_A running on myhost_A will be processed by both log paths, and the messages of application_B running on myhost_B will not be processed at all.

-

If you add the final flag to the first log path, then only this log path will process the messages of myhost_A, so the second log path will receive only the messages of application_A running on myhost_B.

-

If you create a third log path that includes the fallback flag, it will process the messages not processed by the first two log paths, in this case, the messages of application_B running on myhost_B.

-

Adding a fourth log path with the catchall flag would process every message received by the syslog-ng server.

log { source(s_localhost); destination(d_file); flags(catchall); };

The following example shows a scenario that can result in message loss. Do NOT use such a configuration, unless you know exactly what you are doing. The problem is if a message matches the filters in the first part of the first log path, syslog-ng OSE treats the message as 'processed'. Since the first log path includes the final flag, syslog-ng OSE will not pass the message to the second log path (the one with the fallback flag). As a result, syslog-ng OSE drops messages that do not match the filter of the embedded log path.

# Do not use such a configuration, unless you know exactly what you are doing.

log {

source(s_network);

# Filters in the external log path.

# If a message matches this filter, it is treated as 'processed'

filter(f_program);

filter(f_message);

log {

# Filter in the embedded log path.

# If a message does not match this filter, it is lost, it will not be processed by the 'fallback' log path

filter(f_host);

destination(d_file1);

};

flags(final);

};

log {

source(s_network);

destination(d_file2);

flags(fallback);

};Example: Using the drop-unmatched flag

In the following example, if a log message arrives whose $MSG part does not contain the string foo, then syslog-ng OSE will discard the message and will not check compliance with the second if condition.

...

if {

filter { message('foo') };

flags(drop-unmatched)

};

if {

filter { message('bar') };

};

...

(Without the drop-unmatched flag, syslog-ng OSE would check if the message complies with the second if condition, that is, whether or not the message contains the string bar .)

Managing incoming and outgoing messages with flow-control

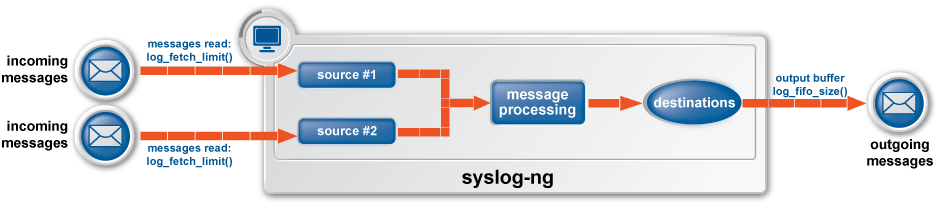

This section describes the internal message-processing model of syslog-ng, as well as the flow-control feature that can prevent message losses. To use flow-control, the flow-control flag must be enabled for the particular log path.

The syslog-ng application monitors (polls) the sources defined in its configuration file, periodically checking each source for messages. When a log message is found in one of the sources, syslog-ng polls every source and reads the available messages. These messages are processed and put into the output buffer of syslog-ng (also called fifo). From the output buffer, the operating system sends the messages to the appropriate destinations.

In large-traffic environments many messages can arrive during a single poll loop, therefore syslog-ng reads only a fixed number of messages from each source. The log-fetch-limit() option specifies the number of messages read during a poll loop from a single source.

Figure 13: Managing log messages in syslog-ng

Every destination has its own output buffer. The output buffer is needed because the destination might not be able to accept all messages immediately. The log-fifo-size() parameter sets the size of the output buffer. The output buffer must be larger than the log-fetch-limit() of the sources, to ensure that every message read during the poll loop fits into the output buffer. If the log path sends messages to a destination from multiple sources, the output buffer must be large enough to store the incoming messages of every source.

TCP and unix-stream sources can receive the logs from several incoming connections (for example many different clients or applications). For such sources, syslog-ng reads messages from every connection, thus the log-fetch-limit() parameter applies individually to every connection of the source.

Figure 14: Managing log messages of TCP sources in syslog-ng

The flow-control of syslog-ng introduces a control window to the source that tracks how many messages can syslog-ng accept from the source. Every message that syslog-ng reads from the source lowers the window size by one, every message that syslog-ng successfully sends from the output buffer increases the window size by one. If the window is full (that is, its size decreases to zero), syslog-ng stops reading messages from the source. The initial size of the control window is by default 100: the log-fifo-size() must be larger than this value in order for flow-control to have any effect. If a source accepts messages from multiple connections, all messages use the same control window.

|

|

NOTE:

If the source can handle multiple connections (for example, network()), the size of the control window is divided by the value of the max-connections() parameter and this smaller control window is applied to each connection of the source. |

When flow-control is used, every source has its own control window. As a worst-case situation, the output buffer of the destination must be set to accommodate all messages of every control window, that is, the log-fifo-size() of the destination must be greater than number_of_sources*log-iw-size(). This applies to every source that sends logs to the particular destination. Thus if two sources having several connections and heavy traffic send logs to the same destination, the control window of both sources must fit into the output buffer of the destination. Otherwise, syslog-ng does not activate the flow-control, and messages may be lost.

The syslog-ng application handles outgoing messages the following way:

Figure 15: Handling outgoing messages in syslog-ng OSE

-

Output queue: Messages from the output queue are sent to the target syslog-ng server. The syslog-ng application puts the outgoing messages directly into the output queue, unless the output queue is full. The output queue can hold 64 messages, this is a fixed value and cannot be modified.

-

Disk buffer: If the output queue is full and disk-buffering is enabled, syslog-ng puts the outgoing messages into the disk buffer of the destination.

-

Overflow queue: If the output queue is full and the disk buffer is disabled or full, syslog-ng puts the outgoing messages into the overflow queue of the destination. (The overflow queue is identical to the output buffer used by other destinations.) The log-fifo-size() parameter specifies the number of messages stored in the overflow queue. For details on sizing the log-fifo-size() parameter, see Managing incoming and outgoing messages with flow-control.

There are two types of flow-control: Hard flow-control and soft flow-control.

-

Soft flow-control: In case of soft flow-control there is no message lost if the destination can accept messages, but it is possible to lose messages if it cannot accept messages (for example non-writeable file destination, or the disk becomes full), and all buffers are full. Soft flow-control cannot be configured, it is automatically available for file destinations.

Example: Soft flow-control

source s_file { file("/tmp/input_file.log"); }; destination d_file { file("/tmp/output_file.log"); }; destination d_tcp { network("127.0.0.1" port(2222) log-fifo-size(1000) ); }; log { source(s_file); destination(d_file); destination(d_tcp); };Caution: Hazard of data loss! For destinations other than file, soft flow-control is not available. Thus, it is possible to lose log messages on those destinations. To avoid data loss on those destinations, use hard flow-control.

-

Hard flow-control: In case of hard flow-control there is no message lost. To use hard flow-control, enable the flow-control flag in the log path. Hard flow-control is available for all destinations.

Example: Hard flow-control

source s_file { file("/tmp/input_file.log"); }; destination d_file { file("/tmp/output_file.log"); }; destination d_tcp { network("127.0.0.1" port(2222) log-fifo-size(1000) ); }; log { source(s_file); destination(d_file); destination(d_tcp); flags(flow-control); };

Flow-control and multiple destinations

Using flow-control on a source has an important side-effect if the messages of the source are sent to multiple destinations. If flow-control is in use and one of the destinations cannot accept the messages, the other destinations do not receive any messages either, because syslog-ng stops reading the source. For example, if messages from a source are sent to a remote server and also stored locally in a file, and the network connection to the server becomes unavailable, neither the remote server nor the local file will receive any messages.

|

|

NOTE:

Creating separate log paths for the destinations that use the same flow-controlled source does not avoid the problem. |

If you use flow-control and reliable disk-based buffering together with multiple destinations, the flow-control starts slowing down the source only when:

-

one destination is down, and

-

the number of messages stored in the disk buffer of the destination reaches (disk-buf-size() minus mem-buf-size()).