SSH hostkeys

SSH communication authenticates the remote SSH server using public-key cryptography, either using plain hostkeys, or X.509 certificates. Client authentication can also use public-key cryptography. The identity of the remote server can be verified by inspecting its hostkey or certificate. When trying to connect to a server via One Identity Safeguard for Privileged Sessions (SPS), the client sees a hostkey (or certificate) shown by SPS. This key is either the hostkey of SPS, or the original hostkey of the server, provided that the private key of the server has been uploaded to SPS. In the latter case, the client will not notice any difference and have no knowledge that it is not communicating directly with the server, but with SPS.

Authenticating clients using public-key authentication in SSH

Public-key authentication requires a private and a public key (or an X.509 certificate) to be available on One Identity Safeguard for Privileged Sessions (SPS). First, the public key of the user is needed to verify the user's identity in the client-side SSH connection: the key presented by the client is compared to the one stored on SPS. SPS uses a private key to authenticate itself to the sever in the server-side connection. SPS can use the private key of the user if it is uploaded to SPS. Alternatively, SPS can generate a new keypair, and use its private key for the server-side authentication, or use agent-forwarding, and authenticate the client with its own key.

|

|

Caution:

If SPS generates the private key for the server-side authentication, then the public part of the keypair must be imported to the server, otherwise the authentication will fail. Alternatively, SPS can upload the public key (or a generated X.509 certificate) into an LDAP database. |

The gateway authentication process

When gateway authentication is required for a connection, the user must authenticate on One Identity Safeguard for Privileged Sessions (SPS) as well.

This additional authentication can be performed:

-

Out-of-band: in a protocol-independent way, on the web interface of SPS.

That way the connections can be authenticated to the central authentication database (for example, LDAP or RADIUS), even if the protocol itself does not support authentication databases. Also, connections using general usernames (for example, root, Administrator, and so on) can be connected to real user accounts.

-

Inband: when the protocol allows it, using the incoming connection itself for communication with the authentication database.

It is the SSH, RDP, and Telnet protocols that allow gateway authentication to be performed also inband, without having to access the SPS web interface.

For SSH and Telnet connections, inband gateway authentication must be performed when client-side authentication is configured. For details on configuring client-side authentication, see Client-side authentication settings.

For RDP connections, inband gateway authentication must be performed when SPS is acting as a Remote Desktop Gateway (or RD Gateway). In this case, the client authenticates to the Domain Controller or a local user database. For details, see Using One Identity Safeguard for Privileged Sessions (SPS) as a Remote Desktop Gateway.

In the case of RDP connections, inband gateway authentication can also be performed if an AA plugin is configured.

Figure 15: Gateway authentication

Technically, the process of gateway authentication is the following:

-

The user initiates a connection from a client.

-

If gateway authentication is required for the connection, SPS pauses the connection.

-

Out-of-band authentication:

The user logs in to the SPS web interface, selects the connection from the list of paused connections, and enables it. It is possible to require that the authenticated session and the web session originate from the same client IP address.

Inband authentication:

SPS requests the username and optionally the credentials for gateway authentication. The user logs in to the SPS gateway.

-

The user performs the authentication on the server.

NOTE: Gateway authentication can be used together with other advanced authentication and authorization techniques like four-eyes authorization, client- and server-side authentication, and so on.

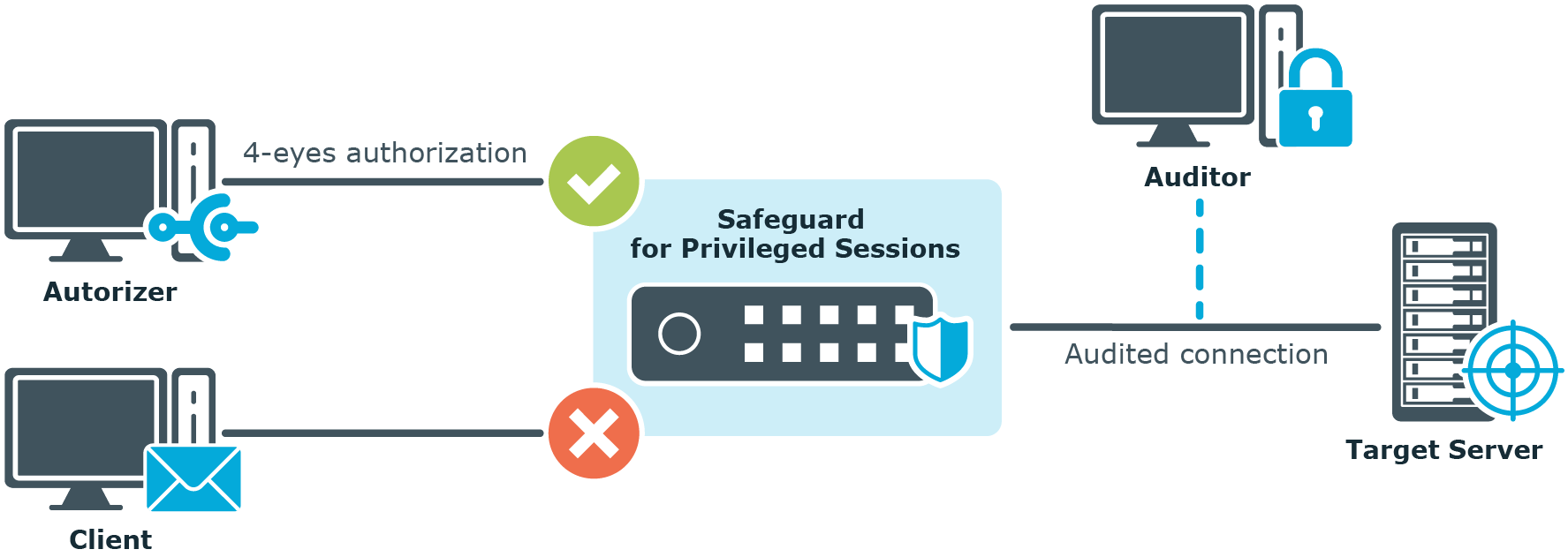

Four-eyes authorization

When four-eyes authorization is required for a connection, a user (called authorizer) must authorize the connection on One Identity Safeguard for Privileged Sessions (SPS) as well. This authorization is in addition to any authentication or group membership requirements needed for the user to access the remote server. Any connection can use four-eyes authorization, so it provides a protocol-independent, out-of-band authorization and monitoring method.

The authorizer has the possibility to terminate the connection any time, and also to monitor real-time the events of the authorized connections: SPS can stream the traffic to the Safeguard Desktop Player application, where the authorizer (or a separate auditor) can watch exactly what the user does on the server, just like watching a movie.

|

|

NOTE:

The auditor can only see the events if the required decryption keys are available on the host running the Safeguard Desktop Player application. |

Figure 16: Four-eyes authorization

Technically, the process of four-eyes authorization is the following:

|

|

NOTE:

Four-eyes authorization can be used together with other advanced authentication and authorization techniques like gateway authentication , client- and server-side authentication, and so on. |

-

The user initiates a connection from a client.

-

If four-eyes authorization is required for the connection, SPS pauses the connection.

-

The authorizer logs in to the SPS web interface, selects the connection from the list of paused connections, and enables it.

-

The user performs the authentication on the server.

-

The auditor (who can be the authorizer, but it is possible to separate the roles) watches the actions of the user real-time.